As the only occupant of Recoleta Cemetery marked with signposts, Sarmiento is widely recognized as one of the most important figures in Argentine history:

Born in 1811 while Argentina struggled for independence, Domingo Sarmiento spent his early years voraciously reading & studying. It would set the tone for his life. By the age of 15, he founded a school in his native province of San Juan… all students were naturally older than he was at the time.

Due to civil war & local caudillo Facundo Quiroga, Sarmiento fled in exile to Chile in 1831 where he continued his educational activities. That period was spent between marriage, founding the Universidad de Chile, running a newspaper, & being sent on behalf of the Chilean government to the United States to study its primary education system.

Sarmiento returned to Argentina 20 years later as an authority in education. Anti-Rosas to the core, he later aligned with Bartolomé Mitre while serving as Senator. Accompanying General Wenceslao Paunero to the Cuyo region, Sarmiento governed his native province of San Juan then returned to the U.S. as Argentina’s ambassador. Unfortunately his adopted son was killed in the War of the Triple Alliance while he was away. Back home in 1868 & under no political party, Sarmiento was elected President with Adolfo Alsina as his running mate. After one term in the Casa Rosada, he continued to serve Argentina in number of governmental & educational posts.

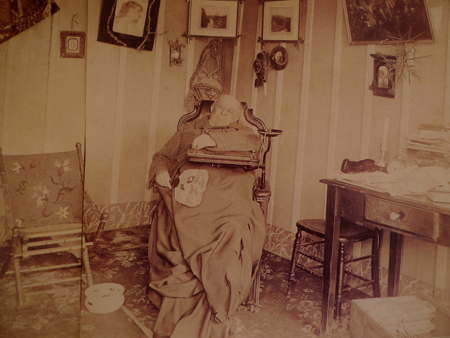

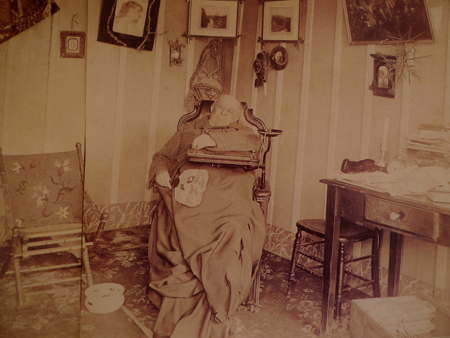

Late in life, Sarmiento moved to Asunción for health reasons. He passed away on Sept 11, 1888, & that day is now commemorated as Teacher’s Day. The most accessible portrait of Sarmiento can be found on an older version of the 50 peso bill, but he was also the subject of one of the most publicized death portraits in Argentine history. Those portraits were commonly used to mark important events & released to the press. Sarmiento “posed” for this photo a few hours after his death surrounded by objects of daily use… including his chamber pot:

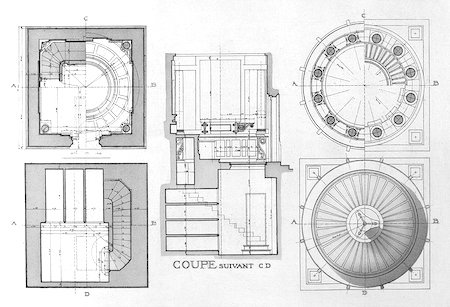

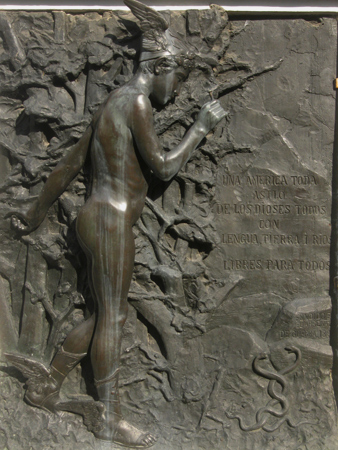

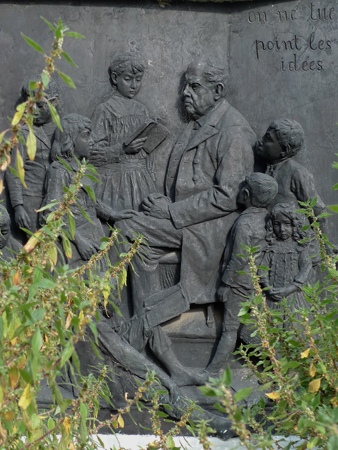

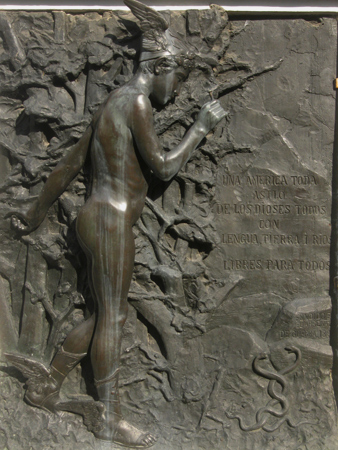

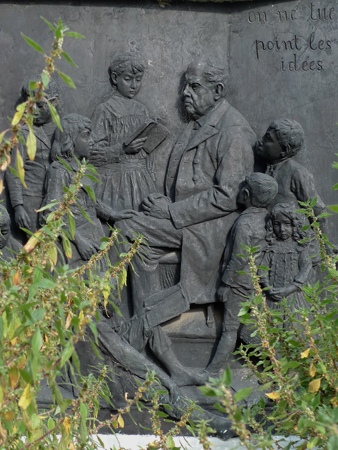

Sarmiento was then brought by boat to Buenos Aires & buried in Recoleta Cemetery. In a crypt designed by Italian sculptor Victor de Pol, the base of the obelisk contains two reliefs: one of Mercury (Roman god of communications) & Sarmiento with children holding books. The French phrase “on ne tue point les idées” was inscribed by Sarmiento on a stone in the Andes Mountains when he fled to Chile: “One never kills ideas”:

Plaques once covered the obelisk itself (as seen below) but were later placed on the side wall when they outnumbered available space. The bust has also been removed. Hidden behind a potted plant is a reminder that Sarmiento once participated in the Grand Lodge of Argentina:

A condor, native to the Andes Mountains & symbolic of Sarmiento’s contributions to Chile & Argentina, crowns the obelisk. At the bird’s feet is a bit of barely legible, cursive text. It reads Civilización y Barbarie, the title of Sarmiento’s definitive work against Quiroga:

Of course Sarmiento was no saint & displayed some negative traits of his time: racism & a bit of an addiction to power. But historians have chosen to focus on the positive. This tomb was declared a National Historic Monument in 1946.